A Lie – SHEH kehr

A Lie – SHEH kehrThe Jewish Book of Formation – Sefer Yetzirah – explains the structure of the universe and the laws of nature, both the physical and metaphysical realms, in six chapters. This is the Jewish mystical system called the Structure of Creation – Ma'aseh Breisheet. The book is itself mystical in the sense that it is concise, figurative, and sometimes poetic. It is also obscure. Neither is it taught in Jewish academies of Torah study.

It is an ancient work. There are discussions whether the book was

authored by the Patriarch Abraham or whether it is

The Book of Formation is based on the creation narrative in the

first chapter of Genesis. There we find that

First there was

These letters were expelled from

All this is contained in the beginning of the first lesson in the Book of Formation.

Because of

The fundamental particles of human speech are consonants and vowels. Hebrew has twenty-two letters which represent the consonants and also ten vowels which are ordinarily not written in holy texts. The Ten Utterances of the first chapter of Genesis consist of these particles. One generation to the next has passed down the skill of how to decipher the particles of the Torah and what they mean. On the surface, the particles and blank spaces between words are a meaningful and coherent narrative. As it is on the surface, the first chapter of Genesis is simple exposition of a simple story.

The Book of Creation calls Space, Time, and Spirit the boundaries of the Universe. Space and Time are tangible realms in that they can be measured, and spirit is a metaphysical realm. The Book of Formation calls these realms World – Olam; Year – Shana; and Soul – Nefesh. This is one of several triads in the Book of Formation.

Space – Olam – has six dimensions. These are the six directions forward, backward, up, down, right, and left. These are six dimensions and not three because no direction is symmetric to another. Consider up and down. One can jump and reach an apex and then fall back down. There is freedom of movement. In contrast, the down direction has no freedom of movement. Under special circumstances, one may step forward and go down stairs, for example. But one must move in this forward direction first. Down and up are clearly not symmetrical. Down is not the negative of up.

Now consider right and left. Let's say that you're standing in the shade of a tree. You move two paces to the right, and you find yourself standing in the sun. Now you return to your original place and take two paces to the left. You find yourself still standing in the shade because you're still under the tree. We find that left is not the negative of right. Two different directions and two different dimensions. World then has six dimensions.

Time – Shana means Year – is like a spiral. The same point returns from time to time. Think of your birthday. Count 365 days and it's your birthday again. Except that you're not in the same place as you were a year before, both figuratively and literally. This circular direction is one dimension. Time also advances forward. Think of the threads on a screw. With each complete turn, the screw returns to the way it was except advanced by one thread. Advancement should not be confused with progress, though. Some societies are well developed, but then devolve. Other societies seem to never develop. They stay the same. So Year has two dimensions.

Soul consists of two embedded dimensions: good and evil. Everything that we say, do, and even think is a mixture of these two extremes.

As I wrote above, World has six dimensions. With the two dimensions of Year and the two dimensions of Soul, Creation has a total of ten dimensions.

Another triad consists of a family surrounding the semantic meaning of the three Hebrew letters peh, ayin, and lamed. The general idea of these three letters is work and effort. In one vowelized form, we have the word po'al – potential energy. Next we have pe'ula – kinetic energy, action, causing. The third of the triad is nif'al – outcome, result, and effect. The template of this triad helps us understand other triads in the Book of Formation.

The Book of Formation continues that the

The second stage of this triad is a scribe – sofer. this is the stage of actualizing. The scribe is copying the book. When it comes to holy books, a scribe copies from a preexisting book and reads it line by line as he copies it. The word sofer also means "counts." A scribe of holy texts checks what he has written by counting the letters to see whether the number in the copy is the same as in the original. For those who have memorized the text of a book, they may dictate it to a scribe to write, or if they write it themselves, they may read it aloud as they write.

The third stage of this triad is story – sippur. This is original material that the reader can form on his or her own. My introduction here is a "story" about the Book of Formation.

At this point I've given you a view of only the first fifteen

words of the book (not including several of

Another triad is three tiers of Hebrew letters. First there are Three "Mothers." These letters are alef, mem, and shin. Alef stands for aveer – air, atmosphere, and weather. Mem stands for mayim – water and other liquids. Shin stands for eish – fire – combustion, oxydation, and heat. The Book of Formation hears fires making hisses like the letter shin even though shin is the second letter of the Hebrew word eish. The human lungs contain these three components – air, moisture, and heat. These letters are the mothers of all speech.

The second tier of letters are the Doublets. These are seven letters that have two sounds, alternating according to Hebrew grammar. A dot is placed in the center of the letter to indicate this second pronunciation. This dot is called a dageish. For example, one doublet is the letter veit which has a /v/ sound. With a dageish, the sound is /b/ and we call the letter beit. Another doublet alternates between the sounds /p/ and /f/ and so for the other five.

These seven doublets correspond to the Sun, the Moon, and the

five planets that are visible to the naked eye. At the same time,

the seven days of the week correspond to the Sun, the Moon,and the

planets. Each heavenly body is ascendant over one day, and then

starting again at the beginning of the next week. For example, the

Sun dominates every Sunday; the Moon over Monday –; read it

This dominance is real according to the Book of Formation. Every day of the week has a different essential quality from the other days. The week must be seven days and uniform whether a society is familiar with the Book of Formation or not. If we were less physical, we could sense which planet was dominant over each day of the week. It would be barely tangible – like smelling a whiff of a scent.

the last tier of letters is the twelve Ordinary letters. These

correspond to the twelve constellations that travel along the

Earth's ecliptic. Each of the twelve constellations occupies 30

degrees of the sky and is dominant over one solar month of thirty

or

The Book of Formation correlates the ten vowels

with the ten fingers and suggests postures for meditation. One

holds the hands with the palms up. Separate the two hands still

facing the body – "five opposite five with the covenant of the

tongue or of nakedness in the middle." The covenant of the tongue

is to not misuse it by speaking malicious gossip or by lying, for

instance. The covenant of the genitals – "nakedness" – is to not

commit incest, rape, adultery or homosexual intercourse. For the

covenant of the tongue in the middle, one raises the hands to the

level of the mouth. One does not join the thumb and index finger,

though. This is an Eastern practice. For the covenant of the

genitals, one sits and places the hands on the thighs palms up.

The Book of Formation says nothing about sitting

Chapter 1 continues with more material which I'm not prepared to introduce. I find this part of the Book of Formation obscure as I do most of Chapters 2 through 6. I'm confident that given time, though, I could master this material. As before, I meditate over small amounts of text for quite a while and apply Talmudic methods until I've reached enough clarity to publish my efforts. In the meantime, I'm sharing the material that I have already deciphered.

To conclude the book, at the end of Chapter 6, there are "three evil things to the tongue." These are: "evil speech, the slanderer, and saying one thing while meaning another." First, I ask the question, how are these three things the fault of the tongue? This are bad personality traits. Therefore, I conclude here that "tongue" refers to language, to speech itself. These three items are problems of bad language. They concern how an issue to be discussed is framed. If the frame is bad, then the conversation is not productive. Maybe even dangerous. This reminds me of the quip in computer circles: "Garbage in, garbage out."

I also don't see "evil" – RAH – as a good translation here since evil is a vile intent rather than merely a problem. There is a word in the semantic family of rah that fits here better. It is rah ’OO ’ah – "unstable" or "shaky." There is a category of dangers that the Talmud calls "soo LAHM rah ’OO ’ah," a ladder that is unstable that someone is liable to fall off of and hurt themselves. This dangerous situation must be removed from one's property. There's another situation in the Talmud where someone loses something small in sand like a coin. It immediately becomes ownerless, and whoever finds it gets to keep it and not search for the owner. Why is the loss considered ownerless? Because it is wishful thinking on the part of the owner that he or she will find it. It's like "looking for a needle in a haystack." The phrase "wishful thinking" in Hebrew is DAH aht rah ’OO ’ah – weak or unstable thinking.

This is not to say that the text should be changed. It is to say that they idea of "bad" in this lesson means "weak." So, a good way of phrasing this lesson is "language has three weak features."

This triad of three weaknesses corresponds to the three phases of potential, action, and outcome. A potential weakness with speech is "weak speech," speech used to frame an issue poorly.

Let's say that there is a debate where it's resolved that Social Security in the U.S. should be abolished because the government should not be handing out welfare money. (This is a real opinion in some libertarian circles and parts of the Republican Party's libertarian-leaning branch.) The semanticist S. I. Hayakawa points out that a similar issue sounds greatly different if reframed as calling "welfare money" "insurance." People have a more positive view of "insurance" than of "welfare." The connotation of "welfare" is negative since it sounds to some like it is undeserved. Connotations are a language problem and, sadly, barely avoidable. "Weak speech" here means framing an issue with a connotation rather than with a denotation.

Truth be told, Social Security is an insurance program. I have in front of me a statement from the Social Security Administration that is called "Retirement, Survivors and Disability Insurance." It's not a trick to call Social Security an insurance program. One pays in premiums and according to knowable rules receives benefits like insurance. It is not like life insurance, though, in the sense that the benefits are paid out while one is still alive and are also variable. Benefits are calculated according to the amount of the premiums paid into the system (based on income over thirty years, if I'm not mistaken).

The action phase associated with speech is hah mahl SHEEN – "the one who activates speech." In ordinary Hebrew, this word is used to describe a slanderer – someone who activates speech for malicious effect. I don't know why this active verb is only used concerning slander, though. Nevertheless, we regard this second phase of the triad as referring back to "weak speech."

The outcome of starting out with framing an issue poorly is "saying one thing and meaning something else in the heart." The lesson here is that even the speaker realizes that he or she has blundered, and the poor frame has led to a conclusion that they didn't intend. Have you ever had the experience where you've explained something thoroughly and someone argues back, and exasperatedly you reply, "But that's not what I mean!" So saying one thing and meaning another in this lesson from the Book of Formation doesn't refer to a devious speaker.

We can see this in the example of Social Security. By framing the program as a form of handing out money to people who don't deserve it, one could conclude that this welfare should be left to private concerns like charities. The message to Americans would be to plan for their retirements during their working years lest they depend on the dole of charities during their later years.

The Book of Formation teaches us another lesson here. Evil – RAH – is unstable and weak. It's not just that behaving evilly shows a weakness in an evildoer to succumb to the lure of misbehavior, but also that evil itself is insubstantial and dangerous. One can fall and be killed. Maybe not physically, but spiritually. Isn't that what we mean falling from grace?

Now the Book of Formation turns to the solidity of good – tohv. "There are three good things about the tongue." To be consistent, tongue here again means language. What are the good things about language? "Silence, good speech, and true speech."

At first glance, we don't give credit to the tongue for silence. This is a result of a person's deliberate decision. "Think before you speak." But this addresses the issue directly. Silence is the first stage – potential – about speaking, to silently think and frame the issue that one feels like talking about. Thinking itself is also a kind of speech – self talk. Actually, it seems to me that it is impossible to silence self talk (except perhaps by hearing someone else speak).

The next phase is actualization, called here "good speech." Once one has thought about what to say and framed the issue carefully – the opposite of "bad speech" (read as weak speech) – one is actually ready to start speaking. The Book of Formation calls this "good speech," meaning strongly founded speech.

Outcome is the last of the three stages. What is the result of

speaking what one feels within a well

In Hebrew, the last word of the Book of Formation is 'true' because what is translated as 'true speech' is literally 'speech true'.

The Book of Formation never concerns itself with the shapes of the written letters; only with their sounds. I'm going to cite the Sages of the Talmud in order to share how they saw that falsehood and truth have lessons for us even from their depiction in print and in writing.

The Sages point out the Hebrew spelling of the word truth – eh MET. The spelling is alef mem tav.

The letter alef (on the right) is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet. Mem (in the middle of the word) is the middle letter of the alphabet. And tav (on the left) is the last letter of the alphabet. The lesson is that truth is the same from the beginning to the end.

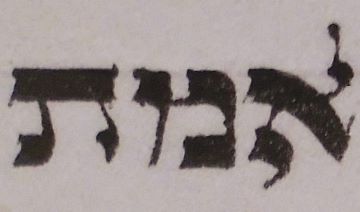

The opposite of truth is falsehood. In Hebrew this word is SHEH kehr, spelled shin koof reish. Hebrew is written from right to left, so the letter on the right is a shin. This shin is written as it is in holy texts. In this case, the photograph of the text was taken from a mezuzah – meh zoo ZAH. Next to it is a koof, then a reish. The Sages call attention to the fact that none of the letters has two legs to stand on. The shin has three legs, but they meet at one point. Because of this, it could fall over. All other representations of a shin that you see in Hebrew texts have flat bottoms and are stable (except a cursive shin).

While the letter koof has two legs, the one on the left is unconnected to the "roof" of the letter. It also protrudes downward beyond the typical lower extent of other letters. Koof is obviously unstable.

We see clearly that the letter reish has only one leg. It is obviously unstable.

A Lie – SHEH kehr

A Lie – SHEH kehrIn contrast, every letter in eh MET (Truth) is stable. Alef has two legs (the letter on the right). Mem, in the middle, has a base that runs along much of the letter and a leg on the left. Tav, the letter on the left, clearly has two legs. Truth is unshakable.

Truth –

eh MET

Truth –

eh METThe Book of Formation's last lesson is the last word of the last chapter of the book – "truth."

And the Book of Formation is truly a grand view of of everything because it is Torah, the blueprint for everything.