Introducing The Gate to Understanding G-d's Unity and the Faith

from Likutei Amarim (the Tanya) * (Bi-Lingual Edition)

Part Two – also called The Education of the Child *

By the grace of G-d

Copyright © 1984, 1965 Kehot Publication Society

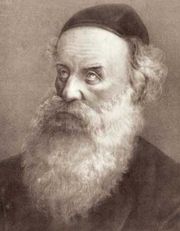

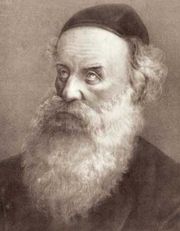

by His Holiness, Grand Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi *

Founder of the Chabad-Lubavitch * school of Hasidism

Sha'ar HaYichud * – The Gate to Understanding G-d's Unity and the Faith

Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Kehot * Publication Society

Brooklyn, New York © 1984

Preface by the Lubavitcher Rebbe *

(to the English rendition of Tanya: Part I)

Chassidus * [Hasidism] in general, and Chabad * Chassidus in particular,

is an all-embracing world outlook and way of life which sees the Jew's central

purpose as the unifying link between the Creator and Creation. [1] The Jew is a creature of "heaven" and of "earth," of

a heavenly Divine soul, which is truly a part of G-dliness, [2] clothed in an earthly vessel constituted of a physical

body and animal soul, whose purpose is to realize the transcendency and

unity of his nature, and of the world in which he lives, within the absolute

Unity of G-d.

The realization of this purpose entails a two-way correlation: one in the

direction from above downward to earth; the other, from the earth upward.

In fulfillment of the first, man draws holiness from the Divinely-given Torah

and commandments, to permeate therewith every phase of his daily life and

his environment — his "share" in this world; [3] in fulfillment

of the second, man draws upon all the resources at his disposal, both created

and man-made, as vehicles for his personal ascendancy and, with him, that

of the surrounding world. One of these basic resources is the vehicle of

human language and communication.

As the Alter Rebbe,* author of the Tanya, pointed out in one of

his other works, [4] any of the "seventy tongues" when

used as an instrument to disseminate the Torah and Mitzvoth, is itself "elevated"

thereby from its earthly domain into the sphere of holiness, while at the

same time serving as a vehicle to draw the Torah and Mitzvoth, from above

downward, to those who read and understand this language.

* * *

In the spirit of the above-mentioned remarks, the volume presented here

— the first English translation of the Tanya (Part I) since its first

appearance 165 years ago — is an event of considerable importance. It brings

this basic work of Chabad philosophy and way of life to a wider range of

Jews, to whom the original work presents a language problem or even a barrier.

It is thus a further contribution to the "dissemination of the fountains"

of Chassidus which were unlocked by Rabbi Israel Ba'al Shem Tov, * who envisaged

Chassidus as a stream of "living waters," growing deeper and wider, until

it should reach every segment of the Jewish people and bring new inspiration

and vitality into their daily lives.

The translation of such a work as the Tanya presents a formidable

task. As a matter of fact, several unsuccessful attempts had been made at

various times in the past to translate the Tanya into one or another

of the European languages. [5] It is therefore to the

lasting credit of Dr. Nissan Mindel that this task has been accomplished.

Needless to say, translations are, at best, inadequate substitutes for

the original. It is confidently hoped, however, that the present translation,

provided as it is with an Introduction, Glossary, Notes and Indexes, will

prove a very valuable aid to students of Chassidus in general, and of Chabad

in particular.

MENACHEM SCHNEERSON

Lag B'Omer, 5722 [Spring 1962]

-----------

Notes to Preface:

- See also Tanya, chaps. 36-37.

- Ibid., beg. chap. 2.

- Ibid., chap. 37.

- Torah Or, Mishpatim, beg.

"Vayyiru . . . k'ma'asei livnas hasapir."

- A translation of all the parts of the Tanya

into Yiddish, by the late Rabbi Uriel Zimmer (olov hasholom) was published

by Otzar Hachassidim Lubavitch and Kehot Publication Society in 1958. An

English translation of the second part of the Tanya appears in The

Way of the Faithful, by Raphael Ben Zion (Los Angeles, 1945), which leaves

much to be desired. A new and revised English translation of it, together

with the other parts of the Tanya, is in preparation by the Kehot

Publication Society. *

* Subsequently, the English translations of all five parts of Tanya

have already been published by the Kehot Publication Society.

Translator's Foreword (from 1965)

Sha'ar HaYichud VeHa'emunah * is the second of the five parts which

constitute Likutei Amarim. An English translation of the first part

of Likutei Amarim (Tanya) by Dr. Nissan Mindel was published by Kehot

Publication Society in 1962, and has since been published in a second edition.

A translation of the other parts of Likutei Amarim is in preparation

by Kehot Publication Society. [These have already been

published, as noted in the Rebbe's preface above.]

A translation, no matter how carefully prepared, cannot do justice to the

original. Yet, the translator has made every effort to preserve the precise

meaning of the original Hebrew text, occasionally at the expense of smoothness

of style.

The translator has included sources and additional notes which serve to

elucidate the text. Additional references have been added for the benefit

of those who, by studying this treatise, are stimulated to pursue the subject

further. The translator's introduction presents in somewhat greater detail

some of the leading ideas of the work. It would be impossible within the

limited space of a few pages to give a complete exposition of the involved

and profound doctrines which constitute Chabad philosophy. For a full account

of these concepts, the reader is referred to the works quoted in the references.

The Preface to the first volume by His Holiness, Grand Rabbi M. Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, has been reproduced here [above]. The Glossary which was published at the end of volume one will also be helpful to the student of the present work.

NISEN MANGEL

Tammuz 6, 5725 [Summer 1965]

Translator's Introduction

Grand Rabbi Schneur Zalman, the author of Sha'ar HaYichud VeHa'emunah,

is the founder of Chabad, the intellectual branch of Chassidism. A major

difference between the teachings of Chabad and those of Chassidism in general

is that Chabad obligates a knowledge of G-dliness in addition to simple faith.

Faith and knowledge, explains Rabbi Schneur Zalman, are each the necessary

complement of the other for proper service of G-d. When one dwells upon the

greatness of G-d and contemplates His wondrous deeds, he/she obtains in a

small measure a conception of His Infinite power. In conceiving Him, he/she

is aroused to love G-d and to cleave to Him and desires to manifest his/her

love by observing His commandments. In the same way, one who considers the

unfathomable essence of the Creator is overcome by a sense of awe and fear

of Him and will refrain from acting in opposition to His Will.

Yet, human knowledge is limited and human intellect cannot visualize what

is beyond it. Therefore, human reason cannot conceive the true essence of

G-d because of His perfection and the imperfection of human reason. However,

one must believe with pure faith the esoteric aspects of G-d which transcend

the intellect. According to Rabbi Schneur Zalman, one must strive to understand

Divinity to the limit of one's intellectual capacities and beyond that limit

one is to believe with simple faith. With the maximum of understanding followed

by faith, one will come to serve G-d with warmth and vitality. [1]

In his introduction to Sha'ar HaYichud VeHa'emunah, called "The

Education of the Child," the author stresses the importance of educating

even the young child to love G-d and have faith in Him. For this will remain

with him/her throughout life and be a sound basis for the ultimate purpose

of his/her life — the fulfillment of his/her religious duties.

The twelve chapters forming the body of Sha'ar HaYichud VeHa'emunah

are a profound exposition of several basic Jewish philosophical concepts.

Among them are creatio ex nihilo [Latin for "creation of the world

from out of nothing"], Divine Providence, His Essence and attributes, His

immanence and transcendence, and the doctrine of Tzimtzum * ["contraction,"

the so-called self-limitation of the Divine Infinite Light]. The central

idea of this work, the pivot around which all the other concepts revolve,

is the principle of Yichud HaShem,* Divine Unity.

Proclamation of this Unity is made daily by Jews in the Scriptural utterance

"Shma Yisrael," * "Hear O Israel, G-d is our L-rd, G-d is One." [2] During the long history of Jewish exile and suffering,

myriads of Jews have given up their lives rather than renounce their faith

in His Unity and Oneness. [3]

The essential meaning of the doctrine of Divine Unity is the belief in

absolute monotheism, i.e., there is but one G-d, with none other besides

Him. It negates polytheism, the worship of many gods, and paganism, the deification

of any finite thing or being or natural force; it excludes dualism, the

assumption of two rival powers of good and evil, and pantheism, which equates

G-d and nature.

Maimonides' interpretation of G-d's Unity emphasizes also that His Essence

and Being is a simple and perfect Unity without any plurality, composition

or divisibility and free from any physical properties and attributes. In

his words:

G-d is One. He is not two or more than two, but One. None of the things

existing in the universe to which the term one is applied is like unto His

Unity; neither such a unit as a species which comprises many units, nor

such a unit as a physical body which consists of parts. His Unity is such

that there is no other unity like it in the world. . . . The knowledge of

this truth is a positive precept, as it is written, "Hear O Israel, G-d

is our L-rd, G-d is One." [4]

The Chassidic interpretation of Unity, based on the Zoharic concepts of

"Lower Level Unity" and "Higher Level Unity," gives it a more profound meaning.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman explains that Divine Unity does not only exclude the

existence of other ruling powers besides the One G-d or of any plurality

in Him, but it precludes any existence at all apart from Him. The universe

appears to possess an existence independent from its Creator only because

we do not perceive the creating force which is its raison d'etre.

All created things, whether terrestial or celestial, exist only by virtue

of the continuous flow of life and vitality from G-d. The creative process

did not cease at the end of the Six Days of Creation, but continues at every

moment, constantly renewing all existence. Were this creating power to withdraw

even for a single moment, all existence would vanish into nothingness, exactly

as before the Six Days of Creation. Thus, the true essence and reality of

the universe and everything therein is but the Divine power within it. This

aspect of Divine Unity is called in the Zohar Yichudah Tata'ah,* Lower

Level Unity.

Although everything is Divinity, it does not mean that G-d is identical

with the world or limited by it. He is immanent in Creation, yet at the same

time He infinitely transcends it. "It is not the essence of the Divine Being,"

declares Rabbi Schneur Zalman, "that He creates worlds and sustains them." [5] For indeed, the creating power by which all existence is brought into being and sustained is only the Divine speech, the words and letters of the Ten Utterances [6] by which the world is created, which is as nothing in relation to His Infinite Being.

Moreover, the Divine speech is united with His Essence in a complete union

even after it has become "materialized" in the creation of the worlds. Thus,

created beings are always "within" their source, i.e., G-d, and are completely

nullified by Him as the rays of the sun are nullified within the sun-globe.

It is only from the perspective of the created beings who are incapable

of perceiving their source, that they appear as independently existing entities.

However, in relation to Him, all creation is naught; there is no existence

whatsoever apart from Him. Therefore, the creation of the universe does

not effect any change in His Unity and Oneness by its existence, for just

as He was alone prior to Creation, so is He One and alone after the Creation.

And this constitutes Yichudah Ila'ah,* Higher Level Unity.

This interpretation of Divine Unity is closely related to another fundamental

doctrine of Chabad Chassidism — the doctrine of Tzimtzum.*

Jewish philosophic and Kabbalistic thought has been deeply concerned with

the seeming contradiction between the Divine attribute of omnipresence and

the existence of the universe. Since G-d is omnipresent and nothing can

exist outside of Him, where was there place for the universe to materialize

at creation? How could the finite world emerge from G-d the Infinite? How

can things which are the antithesis of Divinity exist in His presence?

To solve these problems, His Holiness, Rabbi Yitzchak Luria [the Holy Arizal] * [7] advanced the doctrine of Tzimtzum, the withdrawal

and contraction of the Infinite. [8] He explained that

before the creation of the worlds, G-d filled all "space" [9] and there was no room (possibility) for the existence

of the universe. However, when it arose in His Will to create the worlds,

the Infinite withdrew to the sides, as it were, and a vacuum and empty space

was formed, thereby making room for their existence. Into this space there

emanated from G-d a ray of light [10] which is the source

of all creation. This light and creating force underwent countless Tzimtzumim

which contracted and diminished it until this corporeal and mundane world,

where even things which are in defiance to holiness, were brought into existence.

Thus, according to the Lurianic doctrine of Tzimtzum, Creation was

preceded by the self-limitation of G-d in order to make room for the material

world and everything in it. In post-Lurianic thought, this doctrine received

two interpretations. Some held that Tzimtzum was to be taken literally,

that is to say, G-d actually removed His presence from the space in which

the worlds were subsequently created, created them, and retained His connection

with them through the exercise of His Providence.

To Rabbi Schneur Zalman, such an interpretation was unthinkable. The doctrine

of Tzimtzum, he states, cannot be taken literally for several reasons.

First, Scripture explicitly declares: "'Do I not fill the heavens and the

earth?' says G-d" [11] and "The whole earth is full

of His glory." [12] The Talmud states, "Just as the

soul fills the body so does G-d fill the universe." [13]

Our Sages in the Midrash explain that G-d revealed Himself to Moses from

a bush in order to teach us that there is no place void of His presence,

not even so lowly a thing as a bush. [14] In the Zohar

we find, "There is no place devoid of G-d." [15] Such

statements abound in Scripture and Rabbinic lore.

Secondly, the literal interpretation of this doctrine implies a change

in G-d's omnipresence. Prior to Creation, the Divine presence was ubiquitous;

subsequently, through the process of Tzimtzum, a vacuum was formed

devoid of His presence. Yet, Scripture specifically states, "I, G-d, have

not changed." [16] In addition, "withdrawal" is a phenomenon

of corporeality which cannot be ascribed to G-d, Who is incorporeal.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman's interpretation of Tzimtzum, [17] which has its foundation in Zohar, Kabbalah and the

teachings of the Ba'al Shem Tov, reflects the true spirit and meanings of

the Scriptures, Talmud and Midrash. He explained that there are two kinds

of Divine emanations: [18] a boundless and unlimited

effluence, called in Kabbalah Or En Sof,* the Infinite Light, and

a light of finite order which can give rise to and be confined in finite

existence. [19] To say that His power and light can be

manifested only in infinity and cannot be revealed in finite existence is

to imply a deficiency in His omnipotence and therefore in His absolute perfection.

Both these powers, the infinite as well as the finite, are equal and complementary

aspects of His omnipotence; yet His Essence transcends them both.

Before Creation, by Divine Will, the infinite power was in ascendancy and

the Infinite Light filled all "space" thereby precluding finite existence.

The finite light was absorbed and concealed within the boundless and infinite

Light as the light of a candle is nullified in the brilliance of the sun.

When G-d desired to create the universe, He withdrew His Infinite Light

and concealed it within Himself, allowing the revelation of His finite power

and light and also making room for the emergence of finite existence. This

is the first Tzimtzum — not withdrawal of G-d Himself but only the

concealment of His Infinite Light. Hence Tzimtzum effects no

change in His Essence nor in His omnipresence, merely removing the manifestation

of His Infinite Light from actuality into latency.

But even this finite power, the source of all Creation, which was revealed

as a result of the concealment of the Infinite Light, is itself too abundant

and powerful to give rise to finite beings. It is only after innumerable

Tzimtzumim, which progressively condense and conceal the creative power,

that it is possible for finite and physical matter to exist. Unlike the initial

Tzimtzum which is a complete concealment of the Infinite Light, each

of the subsequent Tzimtzumim is but a gradual diminution of the Divine

light and creative force, and an adaption to the capacity of the endurance

of created beings. By this screening and concealment of the power by which

all things exist, the world appears to enjoy an independent existence, as

if it were apart from G-d. But truly, "The whole earth is full of His Glory"

for all things exist only by virtue of the Divine creating power immanent

in them and endure only because it is screened from their view. Were permission

granted to the eye to see beyond the external physical form, declares Rabbi

Schneur Zalman, then we would perceive only the Divine power that pervades

and animates every created thing and is its true essence and reality.

It is this thought which forms the opening statement of Sha'ar HaYichud

VeHa'emunah — "Know this day and take unto your heart that G-d

is the L-rd in the heavens above and upon the earth below; there is no other,"

[20] i.e., there is nothing apart from Him. This verse

enjoins one to meditate upon this and understand it so well that it becomes

close to one's heart and finds expression in the fulfillment of the Divine

precepts.

NISEN MANGEL

-----------

Notes to Introduction:

- See Likutei Torah by Rabbi Schneur Zalman

of Liadi, Kehot Publication Society (Brooklyn, 1965) [Hebrew]. "VaEthchanan,"

pp. 7 ff.

- Deuteronomy 6:4. See Chapter 1, note 5.

- Cf. Likutei Amarim (Tanya), Kehot Publication

Society (Brooklyn, 1958), Chapters 18-19.

- Maimonides, Yad HaChazakah, "Hilchoth Yesodei

Hatorah," 1:7. Cf. Moreh Nevuchim, I, Chapters 50, 53.

- Torah Or by Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi,

Kehot Publication Society (Brooklyn, 1954) [Hebrew], p. 166a. This rules

out all pantheistic doctrines which would identify or compound G-d with nature.

- See Chapter 1, note 15.

- One of the most famous and influential Kabbalists

of the sixteenth century.

- See Etz Chaim 1:2; beginning of Otzroth

Chaim, Mavoh Shearim, and Emek HaMelech.

- The term "space" is used here in a figurative sense

since space itself is a creation ex nihilo.

- The Divine effluences and emanations are figuratively

called "Lights" because light possesses qualities which are characteristic

of the Divine emanations. For example, the light which radiates from the

sun is nothing compared to the sun itself and the concealment or revelation

of the light reflects no change whatsoever in its source. In the same way,

G-d's Essence infinitely transcends His emanations and is not affected by

them at all. In addition, similar to the Divine emanations, light is always

bound up with its source, and illumines all places without itself being affected.

- Jeremiah 23:24. Cf. Likutei Amarim,

Part IV, "Igeret Hakodesh," Chapter 25.

- Isaiah 6:3.

- Berachot 10a.

- Shemot Rabbah 11:5.

- Tikunim, Tikun 57, p. 91b.

- Malachi 3:6.

- Cf. Torah Or, p. 27a; Likutei Torah,

"Vayikrah," pp. 101 ff.

- See Note 10, supra.

- Even this power is endless and can give rise to

innumerable finite worlds and vivify them forever.

- Deuteronomy 4:39.

His Holiness, Grand Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi

Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi was born 18 Elul 5505 (late summer of 1745). His birthday in 2016 was Wednesday, September 21. His birthday in 2017 will be on Shabbat (Saturday) September 9. More details of his life may be presented here in the future.

He passed away after Napoleon's failed campaign against Moscow during

the winter of 1812-3 — 24 Tevet 5573.

From:

Challenge: an Encounter with Chabad

Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Ladi, by Gershon Kranzler

A brief presentation of the life, the work,and the basic teachings of the Founder of Chabad Chassidism

Based on talks with the Lubavitcher Rabbi, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson

(Brooklyn, New York: Kehot Publication Society, 1975)

Tanya is Rabbi Schneur Zalman's record of twenty years of counselling. While couched in the format of a scholarly discussion and presenting a metaphysical system, this book is the advising voice of a mentor — profound, saintly, yet human and fatherly; demanding, yet reassuring.

(from the jacket of the book Lessons in Tanya)

English Editions

- Practical Tanya: Part Two – Gateway to Unity and Faith

The Tanya of His Holiness, Grand Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi

Adapted by Chaim Miller

– rabbichaimmiller.com

(Brooklyn, New York: Kol Menachem, 2017)

ISBN-13 978-1-934152-37-9

- Lessons in Tanya

The Tanya of His Holiness, Grand Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi

The Gate to Understanding G-d's Unity and the Faith

(Sha'ar HaYichud VeHa'emunah), with Iggeret HaTeshuvah

Elucidated by Rabbi Yosef Wineberg

Translated into English by Rabbi Sholom B. Wineberg

Edited by Uri Kaploun

This edition provides a lucid running commentary to lead the student by the hand

through the text, map out difficult terrain lying ahead, anticipate each

conceptual obstacle, and brief the student on the background knowledge that

Rabbi Shneur Zalman credited to his reader's presumed erudition.

Lessons in Tanya series, volume III

(Brooklyn, New York: Kehot Publishing Society, 1989)

BM198.S483S5213 1989

296.8'33

ISBN 0-8266-0543-5

ISBN 0-8266-0540-0 – the entire set of 5 volumes

CIP 88-6155

- More than two hundred years ago, in the year 1796 (5557), Tanya was published for the first time — and 5,000 printings since have repeatedly invigorated the Jewish world with a message of informed inspiration. In this brief classic, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, (1745-1812) articulated the Chabad-Lubavitch school of Chassidic thought, filtering the mystical teachings of the Baal Shem Tov through the intellectual framework of traditional Jewish scholarship.

- Lessons in Tanya began as a course of weekly lectures delivered over New York radio by noted Chassidic lecturer, Rabbi Yosef Wineberg.

- The Tanya's successor in our days, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, critically examined the prepared Yiddish text of each lecture before it was broadcast, correcting, adding and amending, so that many of the Rebbe's insights and explanatory comments highlight this commentary.

- This is no detached armchair study. Throughout, the commentary pulsates with life, as the student is nudged out of the academician's complacency, and is swept in the quest G-dliness and self-perfection that comprises the Tanya.

- Lessons in Tanya is thus not only a well-lit and accessible gateway to one of Judaism's most cherished treasure-houses, but also the authoritative guide to its riches.

— from the book's back jacket

- Likutei Amarim (the Tanya): Part Two

The Gate to Understanding G-d's Unity and the Faith

by His Holiness, Grand Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi

translated from the Hebrew, with an introduction, by Rabbi Nisen Mangel, M.A.

The original English only edition is still available from the publisher

(Brooklyn, New York: Kehot Publishing Society, 1965, 1976)

Bi-Lingual Edition

The five parts of Tanya with Hebrew text and English translation on facing pages is readily available

(Brooklyn, New York: Kehot Publishing Society, 1965, 1981; revised edition

1984) (originally published by Soncino Press)

ISBN 0-8266-0400-5

LCC 84-82007

Translations have also been rendered into the following languages:

- Italian

- French

- Spanish

- Arabic

- Russian

- Portuguese

- German (only through Chapter 7)

- Yiddish

- The Sustaining Utterance: Discourses on Chasidic Thought

From a transcription of lectures originally delivered in Hebrew

by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

edited and translated by Yehuda Hanegbi

Based on Sha'ar HaYichud VeHa'emunah, by His Holiness, Grand Rabbi Schneur

Zalman, the Alter Rebbe (1745-1813)

(Northvale, New Jersey: Jason Aronson Inc., 1989)

BM198.S4863S74 1989

296.8'3322—dc20 89-6939

ISBN 0-87668-845-8

- Opening the Tanya: Discovering the Moral and Mystical Teachings of a Classic Work of Kabbalah

by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

Hebrew text edited by Meir Hanegbi

Translated by Rabbi Yaacov Tauber

Based on The Tanya, by His Holiness, Grand Rabbi Schneur Zalman, the Alter Rebbe (1745-1813)

(San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003)

BM198.2.S563S7413 2003

296.8'332—dc21 2003-001614

ISBN 978-0-7879-6798-7

Pronunciation Notes:

Likutei Amarim - lee koo TAY ah mah REEM (Assembled Essays)

Tanya - TAHN yuh ("We have learned")

The Education of the Child - Also translated into English as Education of a Child.

Schneur Zalman - SHNAY oor ZAHL min; also spelled "Shneur"

Liadi - lee AH dee, l'yah DEE (the village Lyady, Belarus [Belorussia])

Chabad - khah BAHD

Lubavitch, Lubavitcher - loo BAH vitch, loo BAH vitch er (from the name of the village Lubavitch, Belarus)

Sha'ar HaYichud - SHAH ahr hah YIH khood

Kehot - keh HAWT (publishing society)

Rebbe - REH bee, REH beh (Grand Rabbi)

Chassidus - khah SID uhs (Hasidism)

Alter - AHL tehr (older)

Ba'al Shem Tov - bah ahl SHEM tohv (Master of a Good Name)

VeHa'emunah - vih hah eh MOO nuh

Tzimtzum, Tzimtzumim (plural) - TSIM tsoom, tsim TSOOM mim

Yichud HaShem - YIH khood hah SHEM

Shma Yisrael - SHMAH yiss rah AYL

Yichudah Tata'ah - yih KHOOD uh tah TAW uh

Yichudah Ila'ah - yih KHOOD uh ee LAW uh

Yitzchak Luriah - YITS khahk LOO ree uh

Arizal - ah REE zahl

Or En Sof - awr ayn SOHF